The Institute of High Fidelity Announces:

NEW STANDARD FOR AMPLIFIERS

NEW MEASUREMENTS AND REVISED TEST TECHNIQUES

PROVIDE

MEANINGFUL COMPARISON DATA FOR THE AUDIOPHILE AND ENGINEER

By Daniel von Recklinghausen

IT does not ordinarily come

to the consciousness of the hi-fi enthusiast that most of

the equipment he buys, whether receiver, amplifier, or turntable,

is manufactured to meet a rigid set of specifications, or

standards, which, taken together, constitute the level of

performance these components must attain. These standards

are either the manufacturer's own or those agreed upon with

other manufacturers through their professional association,

the Institute of High Fidelity. The existence of standards

is important not only to the manufacturer of hi-fi equipment,

but to the buyer as well, because they provide a common

basis of discussion and comparison.

In the case of high-fidelity

amplifiers, the Institute standard since 1959 has been its

IHFM-A-200, but the Institute's Amplifier Standards Committee

has now finished work on a revised standard: the IHF Standard

Methods of Measurement for Amplifiers. The new Standard

is an extension and expansion of the old one that it replaces,

adding instructional material, measurements for stereo amplifiers,

and further tests of amplifier characteristics that laboratory

and manufacturing experience have shown to be of importance.

The new Standard has been framed to include not only tube

and transistor amplifiers, but is also purposely phrased

so that any other amplifying devices that may come along

in the future can be accommodated under its terms.

It

is not possible within the space of one short article to

describe and to explain in detail the entire new amplifier

Standard. (The Standard itself is perhaps 10,000 words in

length, and any detailed explanation could easily be three

or four times as long.) However, some of its salient aspects

are worth discussing both from an information point of view

and because they illustrate the IHF Standards Committee's

approach to the entire question of standards.

It

is not possible within the space of one short article to

describe and to explain in detail the entire new amplifier

Standard. (The Standard itself is perhaps 10,000 words in

length, and any detailed explanation could easily be three

or four times as long.) However, some of its salient aspects

are worth discussing both from an information point of view

and because they illustrate the IHF Standards Committee's

approach to the entire question of standards.

Over the years, it has become

increasingly evident to IHF members that the previous amplifier

Standard was inadequate for two principal reasons: (1) two

amplifiers could test the same, but sound radically different;

and (2) additional specification parameters were needed

to provide goals for the engineer working for design improvements.

The solution to both these problems is a more comprehensive

set of tests and measurements, and this is what the new

Standard provides. For example, the old Standard specified

that eleven different aspects of mono amplifier performance

were to be measured and given numerical values. Under the

new Standard, on the other hand, nineteen different numerical

ratings, plus a total of thirty-one different graphs are

established for the complete measurements of an amplifier.

To spend the time necessary to make all these measurements

on every amplifier would of course be impractical. This

problem is recognized-and solved-in the new Standard by

making most of these readings and graphs optional. The complete

set of measurements thus provides ample information for

advance design guidance, and as few as seven of the most

important of them are ample for purposes of specification

and manufacturing. The seven minimum amplifier specifications

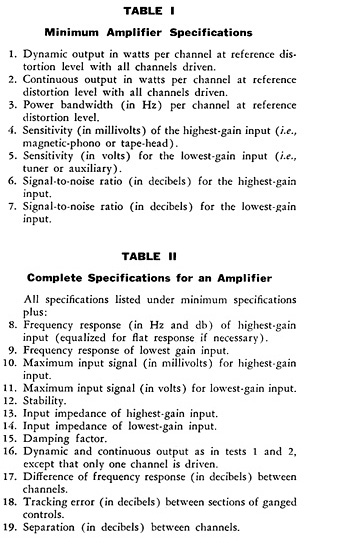

are listed in Table I, the balance in Table II.

One of the most important

characteristics of an amplifier is its output power. In

the immediate past, observers of the audio scene have noticed

the development of a strange situation in which the same

stereo amplifier might be rated-depending upon the whim

of the manufacturer-at anywhere from 15 to over 100 watts.

This situation came about for a variety of reasons, both

commercial and technical, but in any case, new and firm

standards dealing with power and the distortion level at

which it is measured were obviously needed. Even the Electronics

Industries Association (EIA), the trade organization of

the radio and television manufacturers, became convinced

of the necessity of a standard rating method and therefore

established its own amplifier power standard for EIA members

specifying that equipment power ratings be taken at a harmonic

distortion level of 5 per cent. But for high-quality music

reproduction, this 5 per cent figure is much too high. Hi-fi

component manufacturers rate their equipment at distortion

figures ranging from under 1 per cent up to a maximum of

2 per cent.

However, because there is

still a lack of agreement among hi-fi manufacturers as to

the most appropriate distortion level at which to rate an

amplifier, neither the old nor the new Standard specifies

a particular distortion figure at which power is measured,

and it is thus left to the option of the individual manufacturer.

Each manufacturer has therefore chosen what he believes

to be the optimum figure for his own equipment. For example,

if he chooses to rate his amplifier's power at a very low

reference distortion level (say, 0.6 per cent), then the

rated power output will be somewhat lower and the power

bandwidth will be narrower. (The relationship between rated

power and rated distortion at several distortion levels

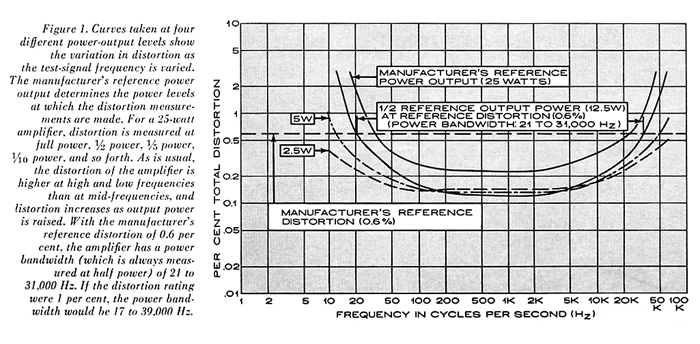

is illustrated by the power-bandwidth graph, Figure 1.)

Under the new Standard, three

steps are necessary to arrive at a power rating: (1) power

with respect to distortion is measured; (2) a curve is drawn;

and (3) the curve is analysed to provide a verbal statement

of the required data. To do this, the manufacturer of the

amplifier decides at what distortion level and at what power

output he wants his amplifier to be rated. These two manufacturer-chosen

reference characteristics for a particular amplifier are

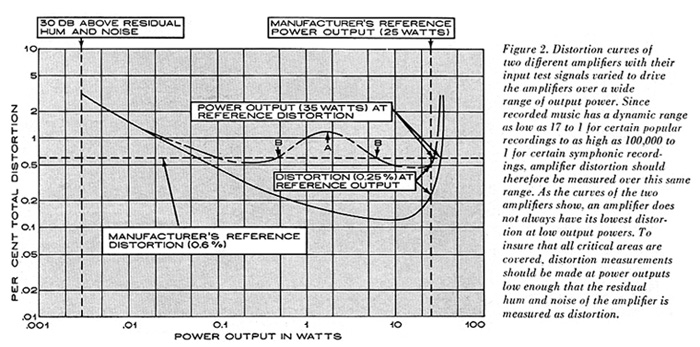

shown as dashed lines on the graph in Figure 2. For purposes

of discussion, let us say that the manufacturer has rated

his amplifier at 25 watts at 0.6 per cent total distortion.

The point on the graph at which the output-power curve derived

from steps (I) and (2) above crosses the horizontal reference

line of 0.6 per cent distortion is the amplifier's rated

output power. As stated in (3) above, the verbal statement

of the specifications is then derived from the graph. In

the example of Figure 2 (solid curve), the amplifier has

bettered the manufacturer's specifications in that at the

manufacturer's rated reference power (25 watts) the amplifier

has 0.25 per cent instead of 0.6 per cent distortion and

at the manufacturer's rated reference distortion (0.6 per

cent) the amplifier is capable of producing 35 instead of

25 watts output. The IHF Standard requires that, in testing,

both these figures be given-the total distortion at the

rated reference power, and the maximum power at the rated

reference distortion.

In some amplifiers, this

crossing of the reference distortion line may take place

not only at some high output power point, but a rise in

distortion may also occur at a low output power (see the

dashed curve in Figure 2). The new IHF Amplifier Standard

requires the listing of this increased percentage of distortion

(1.15 per cent) and the power (1.8 watts) at which it occurs

(points A), and also the two values of power (0.4 watt and

6 watts-indicated as points B) where the reference distortion

line is crossed. This allows a manufacturer or test lab

to make a formal distinction between two amplifiers: one

that has a rising distortion at low-power levels, and one

that does not. Insofar as the manufacturers and test labs

make these new figures available, the buyer is in a much

better position to choose between two amplifiers.

The new amplifier standard

also specifies, as part of its definitions of amplifier

characteristics, the nature of the test equipment to be

used. For example, distortion is defined as the reading

of an instrument that indicates the total residual hum,

noise, and distortion components between 20 and 200,000

Hz. (Hertz, or Hz, is the new term for "cycles per

second" recently adopted by the U. S. Bureau of Standards

and rapidly coming into general use.) Therefore, the distortion

meter responds not only to total harmonic distortion in

the amplifier's output signal, but also to modulation distortion,

oscillation, hum and noise, and everything not a part of

the pure sine-wave test-signal input.

"Power" itself

is also defined in the new Standard, and the various ways

in which amplifier power is described are recognized. There

is continuous power, which an amplifier should be capable

of delivering for at least 30 seconds, quite long enough

to make a measurement and also long enough that any power-supply

instabilities within the amplifier will have disappeared.

The measurement is made individually, one channel at a time,

and also with all channels operating simultaneously. (Reference

is made in the Standard to "all channels" instead

of "both channels" in order not to exclude future

amplifiers that may have more than two.)

Of course, audio amplifiers

are used in the home not for the reproduction of sine waves,

but for the reproduction of music, speech, and other program

material. And unlike a sine-wave test signal, program material

varies constantly in amplitude. Almost every amplifier can

produce a higher power output for a short period of time

than it can for a long period of time-say 30 seconds. Audio

engineers also know that an amplifier may possibly test

well on sine waves, but then, in normal operation with program

material, generate low-frequency transients and other forms

of instability and distortion. The old IHF Amplifier Standard

recognized only that an amplifier could produce more power

while playing music, and therefore set up a "music-power"

measurement by assuming that the amplifier's power-supply

voltages remained constant under the short-term power demands

of normal program material. The measurement of music power

therefore involved maintaining all the supply voltages within

the amplifier at the same values as they would be with no

signal going through the amplifier and then making power

and distortion measurements at leisure. It was felt by the

IHF Standards Committee that this measurement in itself

was neither sufficient nor meaningful. The Committee therefore

prescribed that a second measurement should also be made

using a special switched sine-wave test signal whose waveform

build-up resembles the attack characteristics of music and

speech. Output power and distortion measurements are made

during this "turn-on" period of only a hundredth

of a second by analysing the waveform on a calibrated oscilloscope.

This measurement not only shows up as distortion whatever

harmonics, modulation products, or noise the amplifier produces,

but also indicates any transient instabilities in the amplifier

that might appear with a music signal, but not with a test

signal.

According to the terms of

the new Standard, both of these types of measurement-the

older music-power and the new transient-distortion tests-are

made and curves showing the relationship between output

power and distortion are drawn. The curve yielding the lower

power (or higher distortion)-in other words, the "worst"

curve-is used for the dynamic-power rating of the amplifier,

replacing the older music-power rating. In a stereo amplifier

the two channels are measured separately with a signal applied

to only one channel for single-channel performance, and

a signal applied to all channels simultaneously for multi-channel

performance. Measurements performed in the author's laboratory

and elsewhere have shown that this new dynamic-power measurement

technique is quite effective, in that it provides a far

closer correlation between amplifier measurements and listening

quality than was possible under the old standard.

Power, of course, is only

one of .the many performance aspects of an amplifier; even

the old Standard included such important measurements as

power bandwidth, sensitivity, frequency response, and signal-to-noise

ratio. The new standard specifies all these measurements

and includes performance of controls, interaction between

controls, and so forth. In addition, such other important

information as input impedance, output impedance, and amplifier

stability must be supplied.

The new Standard will help

establish design goals for audio engineers and at the same

time furnish test techniques for validating them. For the

audiophile, the new ratings will make possible a more intelligent

choice among the profusion of amplifiers now available.

Copies of the new IHP Standard Methods of Measurement for

Amplifiers can be obtained from the Institute of High Fidelity,

516 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10036. Price: $2.00.

back to top